Famous Men of the Middle Ages, is a good book with short stories of key people. It’s important for British, European and world history. You can download it free here.

He also wrote some other interesting books.

- Addison B. Poland (1904). Famous Men of Rome. University publishing company.

- Addison B. Poland (1904). Famous Men of the Middle Ages. University Publishing Company.

- Addison B. Poland (1904). Famous Men of Greece.

- Addison B. Poland (1909). Famous Men of Modern Times. American Book Co.

Some interesting things:

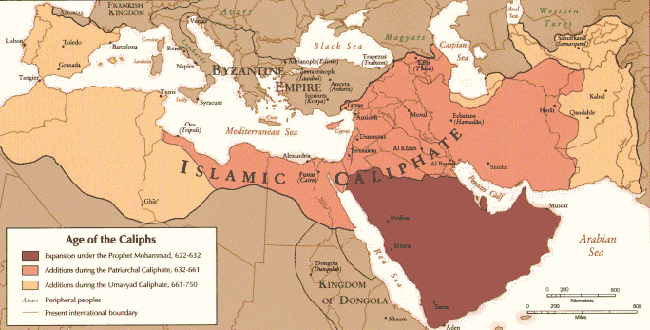

Battle of Tours – October 10, 732 AD

One of the most important battles in history, at this point the moors, muslims had taken over Spain and were advancing into Europe, they attempted conquering France, but in this defeat, it prevented them advancing and taking control of Europe.

At the Battle of Tours near Poitiers, France, Frankish leader Charles Martel, a Christian, defeats a large army of Spanish Moors, halting the Muslim advance into Western Europe. Abd-ar-Rahman, the Muslim governor of Cordoba, was killed in the fighting, and the Moors retreated from Gaul, never to return in such force.

There is some debate about the importance of the battle, with some saying that this was not such a pivotal war, and that the Calighs were over extended anyway.

The Mozarabic Chronicle of 754, a Latin contemporary source which describes the battle in greater detail than any other Latin or Arabic source, states that “the people of Austrasia [the Frankish forces], greater in number of soldiers and formidably armed, killed the king, Abd ar-Rahman”,[15] which agrees with many Arab and Muslim historians. However, virtually all Western sources disagree, estimating the Franks as numbering 30,000, less than half the Muslim force.

‘Abd-al-Raḥmân was a good general, but failed to do two things he should have done before the battle:

- He either assumed that the Franks would not come to the aid of their Aquitanian rivals, or did not care, and he thus failed to assess their strength before the invasion.

- He failed to scout the movements of the Frankish army.

These failures disadvantaged the Muslim army in the following ways:

- The invaders were burdened with booty that played a role in the battle.

- They had casualties before they fought the battle.

- Weaker opponents such as Odo were not bypassed, whom they could have picked off at will later, while moving at once to force battle with the real power in Europe and at least partially pick the battlefield.

The first wave of real “modern” historians, especially scholars on Rome and the medieval period, such as Edward Gibbon, contended that had Charles fallen, the Umayyad Caliphate would have easily conquered a divided Europe. Gibbon famously observed:

A victorious line of march had been prolonged above a thousand miles from the rock of Gibraltar to the banks of the Loire; the repetition of an equal space would have carried the Saracens to the confines of Poland and the Highlands of Scotland; the Rhine is not more impassable than the Nile or Euphrates, and the Arabian fleet might have sailed without a naval combat into the mouth of the Thames. Perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her pulpits might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Mahomet.[44]

Nor was Gibbon alone in lavishing praise on Charles as the savior of Christendom and western civilization. H. G. Wells wrote: “The Moslim [sic] when they crossed the Pyrenees in 720 found this Frankish kingdom under the practical rule of Charles Martel, the Mayor of the Palace of a degenerate descendant of Clovis, and experienced the decisive defeat of [Tours-Poitiers] (732) at his hands. This Charles Martel was practically overlord of Europe north of the Alps from the Pyrenees to Hungary. He ruled over a multitude of subordinate lords speaking French-Latin and High and Low German languages.”[45]

Gibbon was echoed a century later by the Belgian historian Godefroid Kurth, who wrote that the Battle of Tours “must ever remain one of the great events in the history of the world, as upon its issue depended whether Christian Civilization should continue or Islam prevail throughout Europe.”[46]

German historians were especially ardent in their praise of Charles Martel; Schlegel speaks of this “mighty victory”,[47] and tells how “the arm of Charles Martel saved and delivered the Christian nations of the West from the deadly grasp of all-destroying Islam.” Creasy quotes Leopold von Ranke‘s opinion that this period was

one of the most important epochs in the history of the world, the commencement of the eighth century, when on the one side Mohammedanism threatened to overspread Italy and Gaul, and on the other the ancient idolatry of Saxony and Friesland once more forced its way across the Rhine. In this peril of Christian institutions, a youthful prince of Germanic race, Karl Martell, arose as their champion, maintained them with all the energy which the necessity for self-defense calls forth, and finally extended them into new regions.[47]

This goes into more detail of the debate, here.

King Egbert

Egbert (Ecgherht) was the first monarch to establish a stable and extensive rule over all of Anglo-Saxon England. 802 to 839

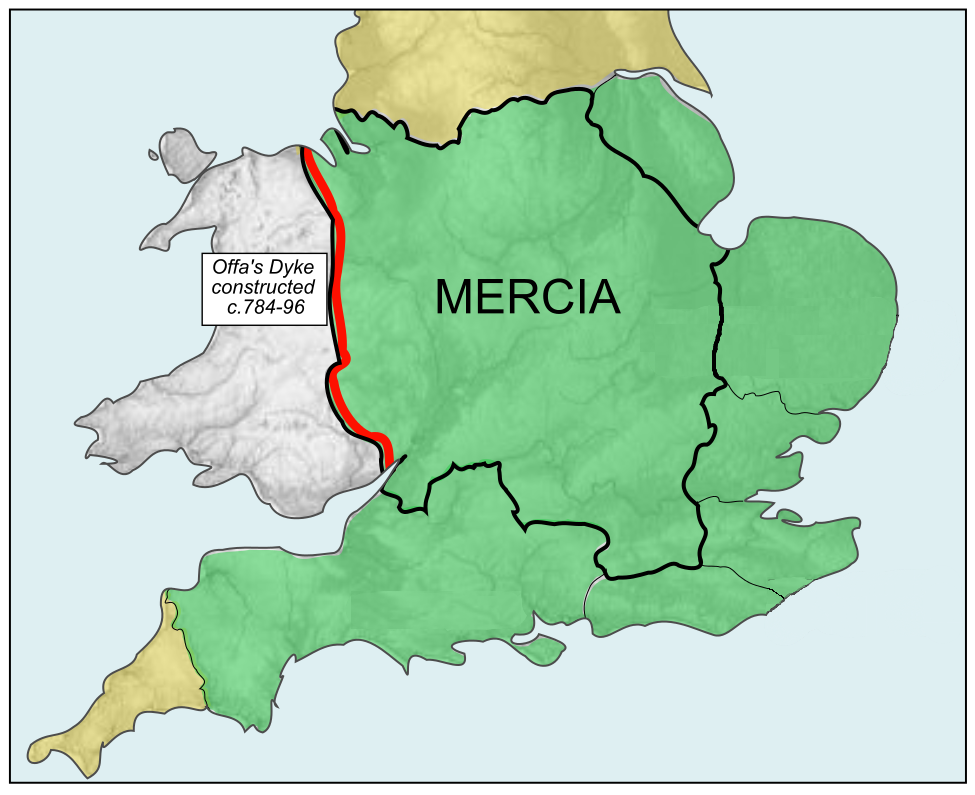

Egbert was the first king of Wessex to completely subdue Mercia and the stability he provided allowed for further development of the kingdom as well as the resources to withstand the Viking raids. At his death, he was so powerful that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles refer to him as Ruler of Britain, not just King of Wessex

In 825 he decisively defeated Beornwulf, king of Mercia, at the Battle of Ellendune (now Wroughton, Wiltshire). The victory was a turning point in English history because it destroyed Mercian ascendancy and left Wessex the strongest of the English kingdoms. By virtue of long-dormant hereditary claims, Egbert was accepted as king in Kent, Sussex, Surrey, and Essex. In 829 he conquered Mercia itself, but he lost it in the following year to the Mercian king Wiglaf. A year before his death Egbert won a stunning victory over Danish and Cornish Briton invaders at Hingston Down (now in Cornwall).

King Athelstan (c. 895 – 939 AD)

Athelstan was the first king of all England, and Alfred the Great’s grandson. He reigned between 925 and 939 AD. A distinguished and courageous soldier, he pushed the boundaries of the kingdom to the furthest extent they had yet reached.

In 927 AD he took York from the Danes, and forced the submission of Constantine, King of Scotland and of the northern kings. All five of the Welsh kings agreed to pay a huge annual tribute. He also eliminated opposition in Cornwall. In 937 AD, at the Battle of Brunanburh, Athelstan led a force drawn from Britain, and defeated an invasion made by the king of Scotland, in alliance with the Welsh and Danes, from Dublin.

Under Athelstan, law codes strengthened royal control over his large kingdom; currency was regulated to control silver’s weight and to penalise fraudsters; buying and selling was largely confined to the burhs, encouraging town life; and areas of settlement in the Midlands and Danish towns were consolidated into shires. Overseas, Athelstan built alliances by marrying off four of his half sisters to various rulers in western Europe.

He was also a great collector of works of art and religious relics, which he gave away to many of his followers and churches in order to gain their support. He died in 939 AD at the height of his powers, and was buried in Malmesbury Abbey. This was a fit burial place for him, as he had been an ardent supporter and endower of the abbey.

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (El Cid) (1045–July 10, 1099)

National hero of Spain, mercenary soldier against Christian and Muslims, ruler of Valencia

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar was not called El Campeador (The Champion) or El Cid (The Lord) for no reason. He had excellent military skills, was never beaten in battles, and successfully repelled the Muslims from invading Spain… even as a corpse.

As the head of his loyal knights, he came to dominate the Levante of the Iberian Peninsula at the end of the 11th century. He reclaimed the Taifa of Valencia from Moorish control for a brief period during the Reconquista, ruling the principality as its Prince (Señorío de Valencia) from 17 June 1094 until his death in 1099. His wife, Jimena Díaz, inherited the city and maintained it until 1102 when it was reconquered by the Moors.

El Cid’s ruled Valencia peacefully for five years until 1099 when the Muslim Almoravids arrived and laid siege to the city themselves. In the course of the siege El Cid now 56 perished from a likely combination of disease and famine. In an attempt to break the siege, his wife, Jimena, ordered that his body be dressed in his armor and he be set upon his horse to lead his troops in one last charge. The Valencian Knights broke out of the gates with El Cid’s corpse in its saddle, the Muslims seeing the dread general coming at them, broke and fled as the Knights cut them down in numbers said to be in the thousands. Horses now spent and their sword arms sore from overuse, the Valencians then encountered fresh Muslim troops rallying to counterattack and withdrew to the city gates again. The Knights had won the battle but did not break the siege and the city fell in 1002 after a siege of three years. El Cid’s wife Jemina was able to escape the city with El Cid’s body and rode into the city of Burgos in Castille with him still in his armor and on his horse where his remains, at last, found their final resting place some three years after his death.

William The Conqueror

After conquering Britain he went back to Normandy, when he returned he found there was some dissent. He enacted stricter laws and also later on the domesday book.

He also created a Curfew law which comes from french: couvre feu (to cover fire).

The law associated with the curfew bell is a custom that history records as being adopted by William I of England[2] in the year 1068.[5][6] The curfew law[1] imposed upon the people was a compulsory duty they had to do or be punished like a criminal.[5] Historians, poets, and lawyers speak of the Medieval law associated with the curfew bell as being levelled mostly against the conquered Anglo-Saxons. It was initially used as a repressive measure by William I to prevent rebellious meetings of the conquered English. He prohibited the use of live fires after the curfew bell was rung to prevent associations and conspiracies. The strict practice of this medieval tradition was pretty much observed during the reign of King William I and William II of England.[7] The law was eventually repealed by Henry I of England in 1103.[8]

A century later in England the curfew bell was associated more with a time of night rather than an enforced curfew law. The curfew bell was in later centuries rung but just associated with a tradition.[7] In Medieval times the ringing of the curfew bell was of such importance that land was occasionally paid for by the service.[9][10] There are even recorded instances where the sound of the curfew bell sometimes saved the lives of lost travellers by safely guiding them back to town.[10]

In Macaulay’s History of Claybrook, Claybrooke Magna, (1791), he says, “The custom of ringing curfew, which is still kept up in Claybrook, has probably obtained without intermission since the days of the Norman Conqueror.