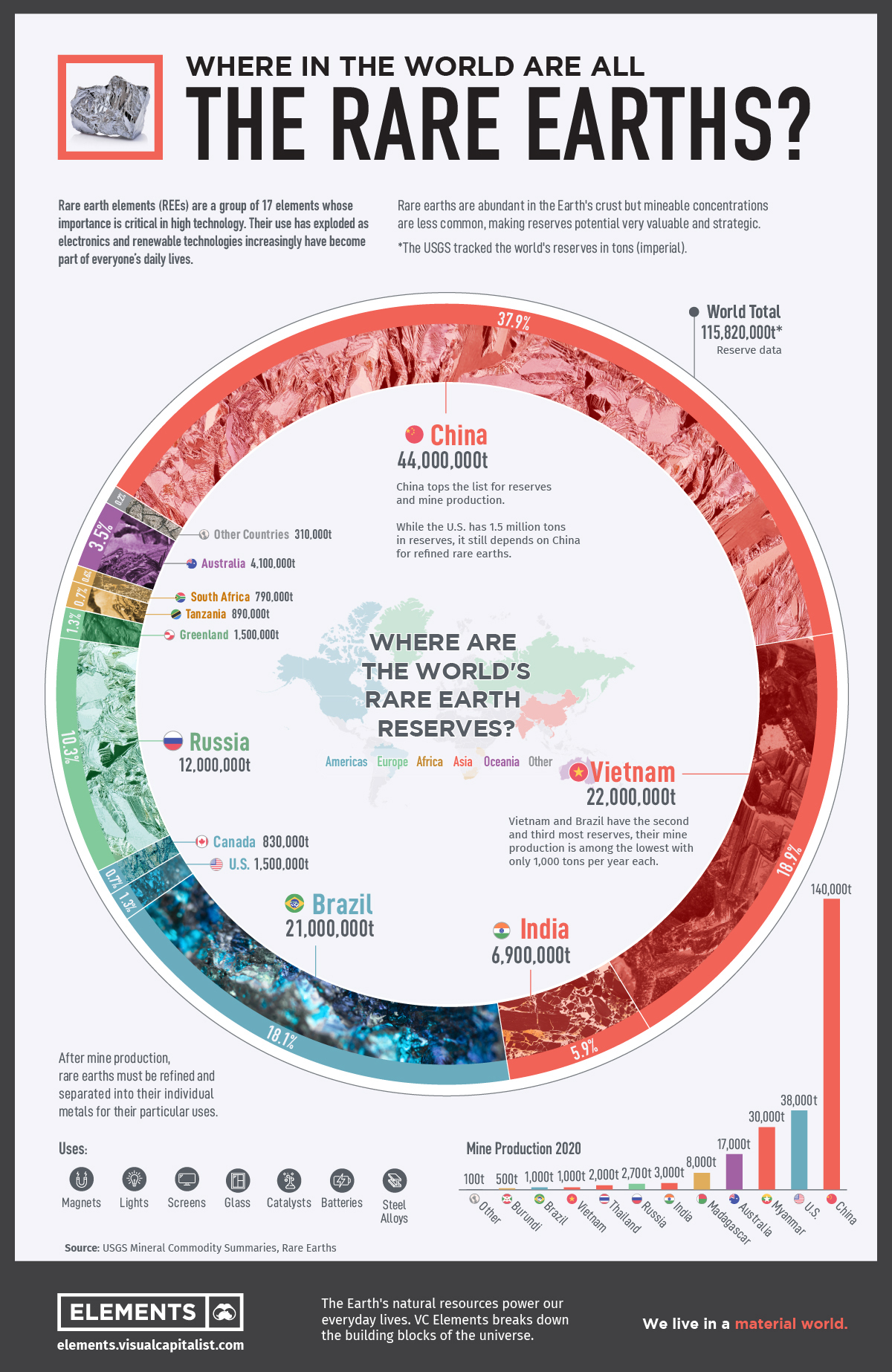

Rare earth metals are extremely important for developing technology. As we develop technology we have a higher demand for these metals, and they could be a key strategic resource for the future. The supply chain for rare earth metals is extremely important for companies and countries.

What are rare metals?

The rare-earth elements (REE), also called the rare-earth metals or (in context) rare-earth oxides, or the lanthanides[1] (though yttrium and scandium are usually included as rare-earths) are a set of 17 nearly-indistinguishable lustrous silvery-white soft heavy metals.[2] Scandium and yttrium are considered rare-earth elements because they tend to occur in the same ore deposits as the lanthanides and exhibit similar chemical properties, but have different electronic and magnetic properties.

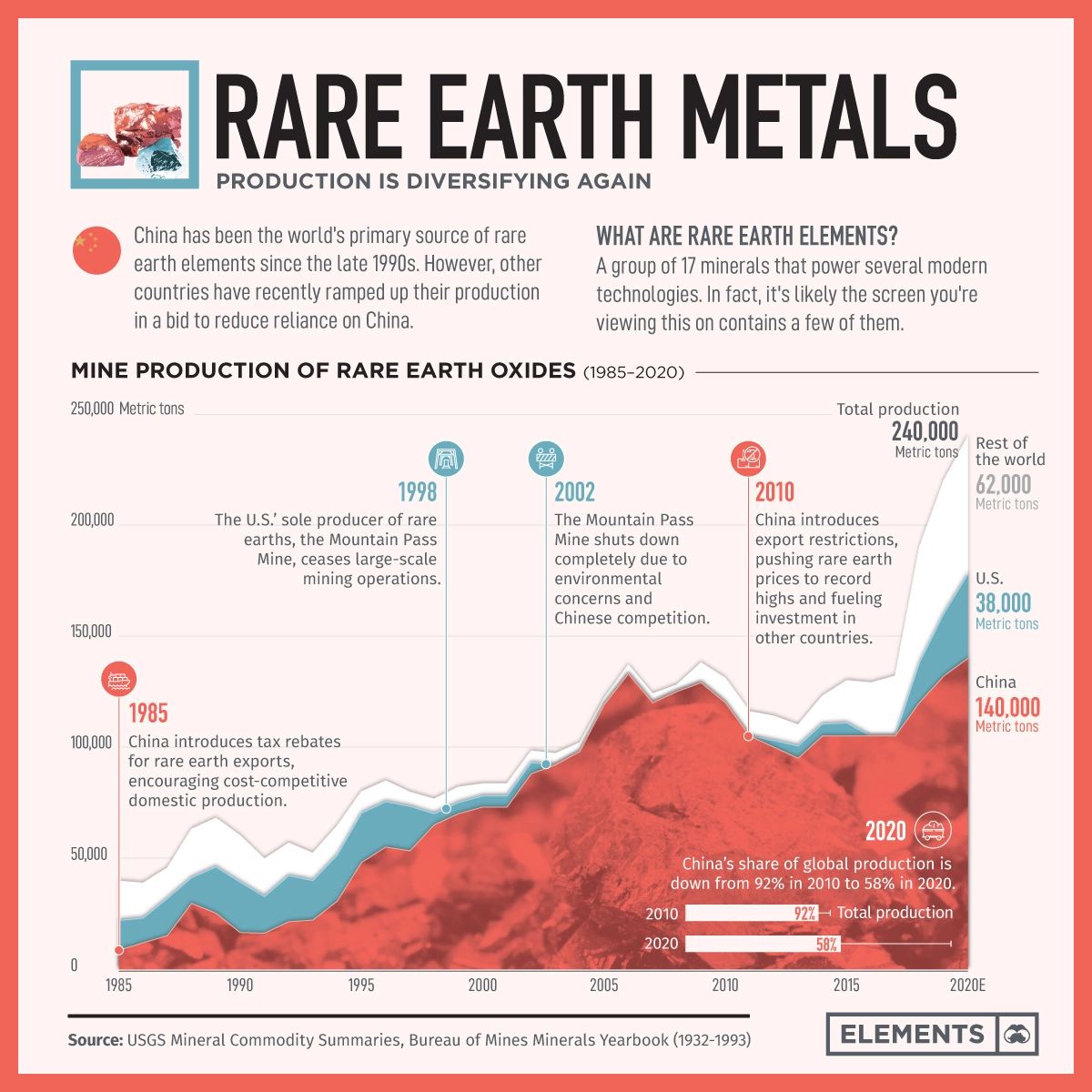

Other countries are ramping up production

What are precious metals?

Precious metals are rare, naturally occurring metallic chemical elements of high economic value. Chemically, the precious metals tend to be less reactive than most elements (see noble metal). They are usually ductile and have a high lustre. Historically, precious metals were important as currency but are now regarded mainly as investment and industrial raw materials. Gold, silver, platinum, and palladium each have an ISO 4217 currency code.

Increased Demand for Metals

We can also confirm that demand for all major metals, except lead, is expected to increase continuously by the end of this century, with the largest growth rate for aluminum (470%), followed by copper (330%), zinc (130%), and iron (100%).

Do we have a shortage?

Prices for most metals and steel have risen in recent weeks as the Ukraine crisis has curbed supplies of some products and complicated delivery logistics. This follows a year of persistent low inventories for key metals, with global copper, aluminum, nickel and zinc markets all registering a deficit in 2021, according to data released last month by the World Bureau of Metals Statistics.

“The metals intensity for the energy transition is very significant,” Weir said. “An electric vehicle needs four to six times as much copper as ICE vehicles, while solar and offshore wind farms need six times as much metal as thermal power generation. Also, for construction, we will need significantly greater amounts of zinc, aluminum, and steel for the energy transition.”

China dominates the processing of battery metals, with around 80% of nickel and cobalt mined for this purpose going into China to produce battery precursor materials “but the front-end supply is not there,” Weir continued.

China and Rare Earth Metals

China has officially cited resource depletion and environmental concerns as the reasons for a nationwide crackdown on its rare-earth mineral production sector.[46] However, non-environmental motives have also been imputed to China’s rare-earth policy.[108] According to The Economist, “Slashing their exports of rare-earth metals… is all about moving Chinese manufacturers up the supply chain, so they can sell valuable finished goods to the world rather than lowly raw materials.

In the words of Deng Xiaoping, a Chinese politician from the late 1970s to the late 1980s, “The Middle East has oil; we have rare earths … it is of extremely important strategic significance; we must be sure to handle the rare earth issue properly and make the fullest use of our country’s advantage in rare earth resources.”

The Best Solution for High Prices is High Prices

As there are shortages of these rare earth metals, the price increases, which attracts more entrants and ways to extract these resources, which solves the problem.

Recycling Metallic Waste

Europe alone produced about 12 million tons of metallic wastes in 2012, and this amount tended to grow more than 4% a year (faster than municipal waste). However, fewer than 20 metals, of the 60 studied by experts of the UNEP, were recycled to more than 50% in the world. 34 compounds were recycled at lower than 1% of the total discarded as trash.

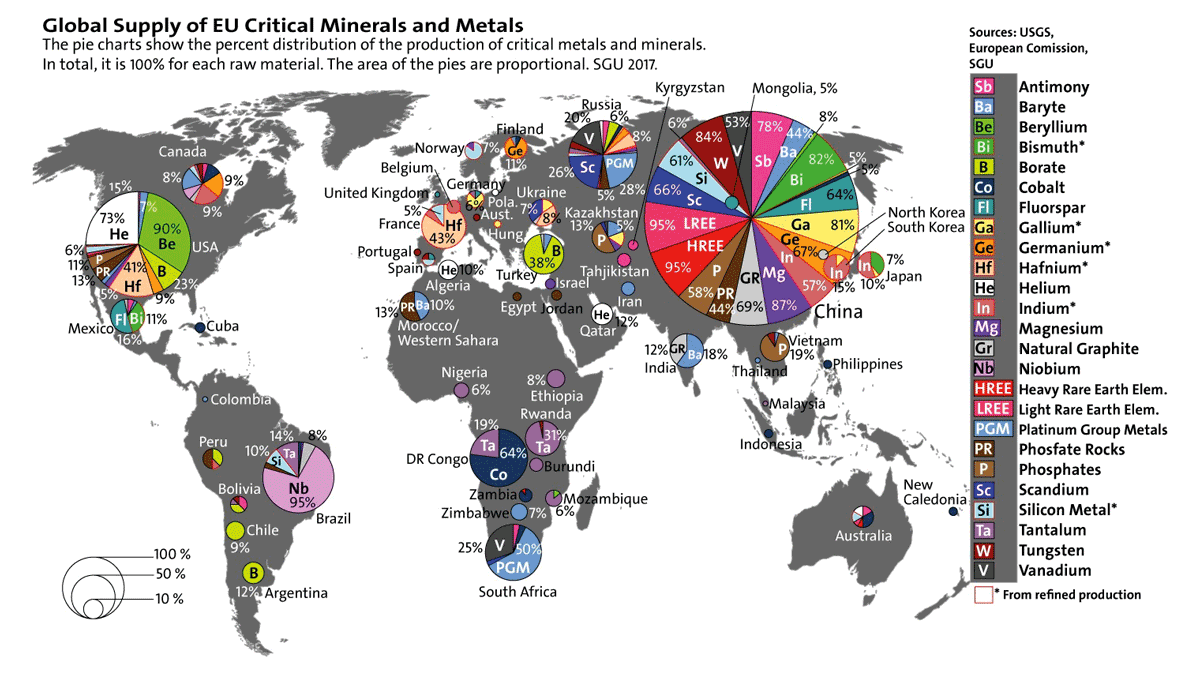

European Strategy

On 3 September 2020, the European Commission presented its strategy to both strengthen and better control its supply of some thirty materials deemed critical, in particular rare earths, in order to lead the green and digital revolution. The list includes, for example:

- graphite, lithium and cobalt, used in the manufacture of electric batteries;

- silicon, an essential component of solar panels;

- rare earths used for magnets,

- conductive seeds and electronic components.

The Commission estimates that the EU will need 18 times more lithium and five times more cobalt by 2030 to meet its climate targets. Many of these materials exist in Europe; the Commission estimates that by 2025 Europe could supply 80% of its automotive industry’s needs. Recycling will be developed.

Where European resources are insufficient, the Commission promises to strengthen long-term partnerships, notably with Canada, Africa and Australia

Lithium

Let’s look at lithium.

Last year, lithium supply fell short of demand by more than 60,000 metric tons. Jennings-Gray’s firm predicts that the deficit will be over 150,000 metric tons by 2030. To meet demand, Benchmark says that $42 billion will need to be invested in the space by the end of this decade.

Lithium prices have surged a staggering 438% above last year. The increase comes as the amount of the metal used has almost quadrupled over the last decade. But the process for extracting lithium, and a relative lack of investment, have yet to catch up with the rising demand.

Without new lithium projects coming online, it’ll likely get worse throughout the 2030s. By 2040, the International Energy Agency expects lithium demand to be 42 times higher than it is today.

Extracting lithium is complicated, involving either mining the ore and then separating the metal or pumping underground water deposits to the surface and then extracting the metal from pools.

“You can build a battery factory in two years, but it takes up to a decade to bring on a lithium project,” Lowry said.

The U.S. plans to ramp up domestic lithium production, but currently produces less than 2% of the world’s supply. Most lithium mines and reserves are located in South America and Australia, with China largely in control of global supply chains.

The lithium supply crunch has not gone unnoticed by electric car manufacturers. Earlier this month, Tesla CEO Elon Musk tweeted about the issue, commenting on what he described as the “insane levels” of lithium prices.

Biggest Lithium Miners in the World

A report from Goldman Sachs stating that lithium prices are overvalued has led to negative sentiment across the lithium sector.

In addition, reports that Warren Buffett-backed electric vehicle company BYD is planning to buy six lithium mines in Africa could have weighed on lithium shares recently.

Similarly, Liontown Resources Limited (ASX: LTR) and Vulcan Energy Resources Ltd (ASX: VUL) shares have also tumbled this year. They are down 27% and 31%, respectively.

However, despite the news weighing down most lithium stocks, not all companies have backtracked in 2022.

In fact, Core Lithium Ltd (ASX: CXO) shares are up 119% while the Allkem Ltd (ASX: AKE) share price has risen 14%.

When looking at the broader market, the S&P/ASX 200 Materials Index (ASX: XMJ) is up 7% this year to date, while the S&P/ASX 200 Index (ASX: XJO) has lost almost 4% over the same period.

Articles

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344920304249

List of elements facing shortage: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_elements_facing_shortage

Lithium and Nickel in shortage: https://fortune.com/2022/04/22/lithium-expert-says-supply-is-not-enough-to-keep-up-with-demand/

Lithium Miners: https://www.mining-technology.com/analysis/top-5-largest-lithium-companies/

US plan to counter China in rare earth metals: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/17/the-new-us-plan-to-rival-chinas-dominance-in-rare-earth-metals.html

More about rare earth metals: https://energyindustryreview.com/metals-mining/upcoming-competition-over-rare-earths-economic-and-strategic-impact/